#the arguments end up sounding like 'historically it has meant x' 'so what

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

The debate about the appropriateness of Jonsa overshadows the political/feudal argument. Unless you can make a convincing case Sansa is going to run away and become a peasant with Sandor (didn't GRRM literally mock that...), or that she can singlehandedly Elizabeth the first it, then you need to be thinking about marriage. Marriage is just as important as war in GRRM's books, if not moreso, and it's a symbolic struggle at that.

Of course Stumpy has searched for Sansa's husband and applied this thinking, but it's one that's otherwise severely lacking. GRRM would go there. We know he'd go there, cousins or not. The question is, why?

Stumpy's Find Sansa's Husband is one of my favs!

No worries! Each of us has a fandom pet peeve we need to rant about. And you're right about Martin's criticism of the "running off with a stable boy trope," in fact, it sounds like the idea really annoys him (his quote below the cut)

And then there are some things that are just don’t square with history. In some sense I’m trying to respond to that. [For example] the arranged marriage, which you see constantly in the historical fiction and television show, almost always when there’s an arranged marriage, the girl doesn’t want it and rejects it and she runs off with the stable boy instead. This never fucking happened. It just didn’t. There were thousands, tens of thousand, perhaps hundreds of thousands of arranged marriages in the nobility through the thousand years of Middle Ages and people went through with them. That’s how you did it. It wasn’t questioned. Yeah, occasionally you would want someone else, but you wouldn’t run off with the stable boy. And that’s another of my pet peeves about fantasies. The bad authors adopt the class structures of the Middle Ages; where you had the royalty and then you had the nobility and you had the merchant class and then you have the peasants and so forth. But they don’t’ seem to realize what it actually meant. They have scenes where the spunky peasant girl tells off the pretty prince. The pretty prince would have raped the spunky peasant girl. He would have put her in the stocks and then had garbage thrown at her. You know. I mean, the class structures in places like this had teeth. They had consequences. And people were brought up from their childhood to know their place and to know that duties of their class and the privileges of their class. It was always a source of friction when someone got outside of that thing. And I tried to reflect that.

I think the issue is, S*nsans and people who shipped Sansa with LF were some of the first to write real meta on her (from what I've heard), so certain fans/perceptions got pretty firmly established, and then a new generation of Sansa fan came along who rejected the Sansa x adult man/molester ships, but it was pretty easy for them to assume that due to Sansa's age, Martin would leave her marriage to the future.

Also, a lot of people don't expect Sansa to be QitN, so the succession issue isn't putting pressure on the marriage timeline, and if you're someone who thinks Bran will actually be king over all Westeros or Rickon will be KitN etc etc, you can imagine Sansa's endgame is safety in Winterfell, not a romance or marriage.

Personally, I think Sansa's interactions with Cersei and LF indicate that she wants to be the right kind of queen (in defiance of Cersei's advice) and is being equipped with tools to achieve her own ends / play the game, for the right reasons, to good ends, but being handed tools nonetheless. She is so unfocused on her birthright and power, it seemed like she was meant to be contrasted with Cersei and Dany. The natural endpoint of that imo would be her becoming queen. And, if she is queen, I've argued that based on other queen's experiences, we must see her married as being a queen is a whole new set of risks, not a happy ending in and of itself.

Of course, some have speculated that the endgame will be indicated, not actually chronicled on the page, as in, Jon and Sansa fall in love, but Jon does get sent to the wall or goes into exile for a callback of what Sansa imagined she could do to save Ned, and we end kinda knowing, eventually they'll get back together, but the actual happy ending isn't on the page. Or the alternative scenario is that Jon is named KitN because of Robb's Will and marries Sansa to resolve all the chaos after parentage reveal. That's where your thoughts on the political aspect of marriage comes in because that would be very tidy. Actually, whoever is recognized by the Northern Lords, whether it’s my preference of Sansa or Jon, the heir issue was a big deal for Robb, so marriage / heirs will certainly come up and impact the plot.

As for Jonsa itself and it being icky to some, I've said before, I think Martin must have something he wants to do with incest beyond showcasing how toxic it is. As in, that is not a way to challenge the reader, by saying something we all know, and his whole shtick is to write complexity into every relationship, every hero, even many villains, so I don't for a minute believe that's he's introduced this topic without planning to ask the audience to think a little more deeply on it. To force us to look at it from a different angle. The way he does that is to give us heroes who are tempted and make us squirm until we get parentage reveal.

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

the main reason i don’t take “i’m a native speaker of the source language” as the be-all, end-all for translation arguments in fandom specifically (as in, between fans who are not professional or even hobbyist translators) is bc, well. sometimes.......... native speakers............ are bad at their own language, too.

#we're on tumblr. we've seen the reading comprehension on this site which is mostly americans whose native language is ostensibly english#alternatively i don't take 'i asked someone who is a native speaker of the source language' as the be-all end-all of t/l arguments#like yes ofc native speakers opinions should be considered. and if i didn't speak any of the source language then fuck man#i'm not qualified to argue with them LOL. but this post is mostly me thinking abt things w/cn origin#bc i've been told my whole life my mom is Very Highly Educated in chinese language arts and speaks appropriately#and it's still pretty frustrating when she tries to make me speak in the same kind of language bc i just don't hear it around that often#but i think it has at least taught me to *think* abt things in that kind of Highly Educated highly-referential/symbolic way#even if i lack the knowledge base of references/symbols to utilize it myself i can go digging for them when t/l from cn --> en#which i think is pretty interesting bc it places me in this kind of 'historically this is what the word has meant' pov#which is just not smth we really do/consider in english esp when looking at modern texts but i think is rlly necessary in chinese#even when looking at texts written in the modern day! and thinking abt it that's probably the source kernel for some gnshn discourse#bc cn is such a context-heavy language; context which goes beyond the meaning of the bare words on the page#bc en doesn't consider historical context of words we're not used to reading into words w/different historical nuances#and since deciding whether the historical or the modern connotations should apply in a certain context is a Skill#the arguments end up sounding like 'historically it has meant x' 'so what? it means y in the modern day'#'yes but the historical meaning adds depth and nuance that changes the interpretation in this context' 'why should it tho?'#and the answer to that is just bc that's how it goes in the language!! Sometimes Other Languages And Cultures Do Things Differently!#anyway this kind of thinking definitely also affects how i write; with all the highly deliberate word choices#and occasional referential nature of my phrasing and whatnot. i like to imagine i have a somewhat chinese writing style in english#like not entirely. i don't craft my native english sentences the way i would craft an english translation of a chinese sentence#the latter of which i typically try to keep similar to the way cn sentences flow which is Different from good en sentence flow#but the extremely specific wording at times and trying to pack a lot of meaning into a few choice words using external context/references#that feels like something i can bring into my english writing and have it read as an english work w/echoes of another language hidden under#花���

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

What draws you to incest ?

*sighs* Ok, here we go. I'm a real card carrying Jonsa now aren't I?

Anon, listen. I know this is an anti question that gets bandied about a lot, aimed at provoking, etc, when we all know no Jonsa is out here being all you know what, it really is the incest, and the incest alone, that draws me in. I mean, come on now. Grow up.

If I was "drawn" to incest I'd be a fan of Cersei x Jaime, Lucrezia x Cesare, hell Oedipus x Jocasta etc... but I haven't displayed any interest in them now, have I? So, huh, it can't be that.

Frankly, it's a derivitive question that is really missing the mark. I'm not "drawn" to it, though yeah, it is an unavoidable element of Jonsa. The real question you should be asking though, is what draws GRRM to it? Because he obviously is drawn to it, specifically what is termed the "incest motif" in academic and literary scholarship. That is a far more worthwhile avenue of thinking and questioning, compared with asking me. Luckily for you though anon, I sort of anticipated getting this kind of question so had something in my drafts on standby...

You really don't have to look far, or that deeply, to be hit over the head by the connection between GRRM's literary influences and the incest motif. I mean, let's start with the big cheese himself, Tolkein:

Tolkein + Quenta Silmarillion

We know for definite that GRRM has been influenced by Tolkein, and in The Silmarillion you notably have a case of unintentional incest in Quenta Silmarillion, where Túrin Turambar, under the power of a curse, unwittingly murders his friend, as well as marries and impregnates his sister, Nienor Níniel, who herself had lost her memory due to an enchantment.

Mr Tolkein, "what draws you to incest?"

Old Norse + Völsunga saga

Tolkein, as a professor of Anglo-Saxon, was hugely influenced by Old English and Old Norse literature. The story of the ring Andvaranaut, told in Völsunga saga, is strongly thought to have been a key influence behind The Lord of the Rings. Also featured within this legendary saga is the relationship between the twins Signy and Sigmund — at one point in the saga, Signy tricks her brother into sleeping with her, which produces a son, Sinfjotli, of pure Völsung blood, raised with the singular purpose of enacting vengence.

Anonymous Norse saga writer, "what draws you to incest?"

Medieval Literature as a whole

A lot is made of how "true" to the storied past ASOIAF is, how reflective it is of medieval society (and earlier), its power structures, its ideals and martial values etc. ASOIAF, however, is not attempting historical accuracy, and should not be read as such. Yet it is clearly drawing from a version of the past, as depicted in medieval romances and pre-Christian mythology for instance, as well as dusty tomes on warfare strategy. As noted by Elizabeth Archibald in her article Incest in Medieval Literature and Society (1989):

Of course the Middle Ages inherited and retold a number of incest stories from the classical world. Through Statius they knew Oedipus, through Ovid they knew the stories of Canace, Byblis, Myrrha and Phaedra. All these stories end more or less tragically: the main characters either die or suffer metamorphosis. Medieval readers also knew the classical tradition of incest as a polemical accusation,* for instance the charges against Caligula and Nero. – p. 2

The word "polemic" is connected to controversy, to debate and dispute, therefore these classical texts were exploring the incest motif in order to create discussion on a controversial topic. In a way, your question of "what draws you to incest?" has a whiff of polemical accusation to it, but as I stated, you're missing the bigger question.

Moving back to the Middle Ages, however, it is interesting that we do see a trend of more incest stories appearing within new narratives between the 11th and 13th centuries, according to Archibald:

The texts I am thinking of include the legend of Judas, which makes him commit patricide and then incest before betraying Christ; the legend of Gregorius, product of sibling incest who marries his own mother, but after years of rigorous penance finally becomes a much respected pope; the legend of St Albanus, product of father-daughter incest, who marries his mother, does penance with both his parents but kills them when they relapse into sin, and after further penance dies a holy man; the exemplary stories about women who sleep with their sons, and bear children (whom they sometimes kill), but refuse to confess until the Virgin intervenes to save them; the legends of the incestuous begetting of Roland by Charlemagne and of Mordred by Arthur; and finally the Incestuous Father romances about calumniated wives, which resemble Chaucer's Man of Law's Tale except that the heroine's adventures begin when she runs away from home to escape her father's unwelcome advances. – p. 2

I mean... that last bit sounds eerily quite close to what we have going on with Petyr Baelish and Sansa Stark. But I digress. What I'm trying to say is that from a medieval and classical standpoint... GRRM is not unique in his exploration of the incest motif, far from it.

Sophocles, Ovid, Hartmann von Aue, Thomas Malory, etc., "what draws you to incest?"

Faulkner + The Sound and the Fury, and more!

Moving on to more modern influences though, when talking about the writing ethos at the heart of his work, GRRM has famously quoted William Faulker:

His mantra has always been William Faulkner’s comment in his Nobel prize acceptance speech, that only the “human heart in conflict with itself… is worth writing about”. [source]

I’ve never read any Faulker, so I did just a quick search on “Faulkner and incest” and I pulled up this article on JSTOR, called Faulkner and the Politics of Incest (1998). Apparently, Faulkner explores the incest motif in at least five novels, therefore it was enough of a distinctive theme in his work to warrant academic analysis. In this journal article, Karl F. Zender notes that:

[...] incest for Faulkner always remains tragic [...] – p. 746

Ah, we can see a bit of running theme here, can't we? But obviously, GRRM (one would hope) doesn’t just appreciate Faulkner’s writing for his extensive exploration of incest. This quote possibly sums up the potential artistic crossover between the two:

Beyond each level of achieved empathy in Faulkner's fiction stands a further level of exclusion and marginalization. – pp. 759–60

To me, the above parallels somewhat GRRM’s own interest in outcasts, in personal struggle (which incest also fits into):

I am attracted to bastards, cripples and broken things as is reflected in the book. Outcasts, second-class citizens for whatever reason. There’s more drama in characters like that, more to struggle with. [source]

Interestingly, however, this essay on Faulkner also connects his interest in the incest motif with the romantic poets, such as Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron:

As Peter Thorslev says in an important study of romantic representations of incest, " [p]arent-child incest is universally condemned in Romantic literature...; sibling incest, on the other hand, is invariably made sympathetic, is sometimes exonerated, and, in Byron's and Shelley's works, is definitely idealized.” – p. 741

Faulkner, "what draws you to incest?" ... I mean, that article gives some good explanations, actually.

Lord Byron, Manfred + The Bride of Abydos

Which brings us onto GRRM interest in the Romantics:

I was always intensely Romantic, even when I was too young to understand what that meant. But Romanticism has its dark side, as any Romantic soon discovers... which is where the melancholy comes in, I suppose. I don't know if this is a matter of artistic influences so much as it is of temperament. But there's always been something in a twilight that moves me, and a sunset speaks to me in a way that no sunrise ever has. [source]

I'm already in the process of writing a long meta about the influence of Lord Byron in ASOIAF, specifically examining this quote by GRRM:

The character I’m probably most like in real life is Samwell Tarly. Good old Sam. And the character I’d want to be? Well who wouldn’t want to be Jon Snow — the brooding, Byronic, romantic hero whom all the girls love. Theon [Greyjoy] is the one I’d fear becoming. Theon wants to be Jon Snow, but he can’t do it. He keeps making the wrong decisions. He keeps giving into his own selfish, worst impulses. [source]

Lord Byron, "what draws you to—", oh, um, right. Nevermind.

I'm not going to repeat myself here, but it's worth noting that there is a clear through line between GRRM and the Romantic writers, besides perhaps melancholic "temperament"... and it's incest.

But look, is choosing to explore the incest motif...well, a choice? Yeah, and an uncomfortable one at that, but it’s obvious that that is what GRRM is doing. I think it’s frankly a bit naive of some people to argue that GRRM would never do Jonsa because it’s pseudo-incest and therefore morally repugnant, no ifs, no buts. I’m sorry, as icky as it may be to our modern eyes, GRRM has set the president for it in his writing with the Targaryens and the Lannister twins.

The difference with them is that they knowingly commit incest, basing it in their own sense of exceptionalism, and there are/will be bad consequences — this arguably parallels the medieval narratives in which incest always ends badly, unless some kind of real penance is involved. For Jon and Sansa, however, the Jonsa argument is that they will choose not to commit incest, despite a confused attraction, and then will be rewarded in the narrative through the parentage reveal, a la Byron’s The Bride of Abydos. The Targaryens and Lannisters, in several ways excluding the incest (geez the amount of times I’ve written incest in this post), are foils for the Starks, and in particular, Jon and Sansa. Exploring the incest motif has been on the cards since the very beginning — just look at that infamous "original" outline — regardless of whether we personally consider that an interesting writing choice, or a morally inexcusable one.

Word of advice, or rather, warning... don't think you can catch me out with these kinds of questions. I have access to a university database, so if I feel like procrastinating my real academic work, I can and will pull out highly researched articles to school you, lmao.

But you know, thanks for the ask anyway, I guess.

#cappy's thoughts#I'm still on my break/hiatus#i just had some of this already written#jonsa#jon x sansa#anti bs#grrm and medieval literature#grrm and william faulkner#grrm and the romantics#grrm and tolkein#grrm and old norse literature#grrm and his literary influences#was this petty lmao?

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

EXT. The Roof (Winter) - Sunset

Not Just Attracted to Women!Peter Maximoff x Fem and Not Just Attracted to Men!Reader

Based off of a dream I recently had: Peter and Y/N have a conversation on the roof of Xavier's in mid-December. Peter accidentally lets it slip that he might not be straight, and he is afraid that Y/N will think less of him because of it because this is the 80s. Y/N reveals that she is also not straight, and is saddened by the fact that Peter could think that she could ever hate him- especially for that. She calls him wonderful. Feelings ensue. Also, a touch of Cherik at the end because I give the people what they want.

Warnings: Swearing, Peter cries, internalized homophobia (this is the 80s-ish and Peter uses the word 'queer' in a kind of incorrect and kind of offensive manner, but it was internalized homophobia and not actually intended to be mean to anyone but himself so I forgive him), a touch of angst but mostly fluff, Charles called you two "children" even though you are obviously not, Erik is happy that his son has someone that cares about him the way you do, Peter is insecure but not super blunt about it, Peter has been deprived of being adored his entire life, bad writing, I mention a serial killer twice, historical inaccuracy because the word queer was still a slur so yeah.

A/N: This is literally the first thing I have ever written so please be nice to me, I wrote this instead of an essay. I would love a comment of any kind, even if it's just a heart emoji or something, and constructive criticism would be highly appreciated. Also 'N/N' stands for nick-name.

(Ok, so, full discloser: the format is odd. The bullet points represent dialogue, and the only dialogue is between you two love birds. The first bullet point is Peter, the second is Y/N, the third is Peter, and so on.)

“I dunno, the whole ‘liking people’ thing has always been weird for me.”

“How do you mean?"

“Pppffftt- 'how do you mean,' what are you, Shakespeare or somethin’?”

“Yeah, because that’s the era when ‘how do you mean' would have been a popular term. Ok, what do you mean?”

“Just- when other people were liking people I never really was?”

He was gesturing wildly and avoiding eye contact, as always. He wasn't uncomfortable with eye contact, he just got bored easily in conversations, he needed to keep himself occupied. In this situation that meant staring at the red and green lights covering the rest of the roof, the snowy trees all over the yard, and a holly garland around the gate. Peter wasn't Christian, but man, did he love their Christmas decorations.

“Like… now? In school?”

“Well- yeah… but also when I was younger. And I never liked the right people? Or... liked them in the right way?”

“So you’ve never liked anyone.”

“No, no… I definitely have. It was just… weird! I don't-”

His hands dropped to his side in defeat.

“I don’t think it’s that out of the ordinary. I would tell you if it was. Also, if it was... 'weird', like you said, that wouldn’t mean it was necessarily bad.”

He hadn’t really heard what she said, he was too busy pondering what his next sentence would be. When she wasn't speaking, he was rambling.

"I had some of the normal crap… like in movies when they talk about the fluttery stomach junk. I've had that around a few girls I've been friends with, also that phase with the boy stuff, a-"

“Wait, what phase with the boy stuff?”

“Like- when you’re in middle school or whatever and you're gay for a second.”

His phrasing was a joke, but the statement as a whole was not.

“…‘Gay for a second’?”

“…Yeah?”

“Hmmm..."

"Is that- not-"

"I don't think that is... 'normal'... per-say..."

“Oh… Really?”

His heart sunk.

“…Yeah.”

“Huh.”

“…Mhm.”

“…Shit.”

He suddenly looked almost embarrassed. He shifted his posture, seemingly trying to shrink into himself.

“Do you... wanna chat about it?”

Panic started to slowly rise in him.

“Um- forget I said anything.”

“Why?”

Something in him said to go on the "defense". He did not appear as calm as he was intending to.

“I’m not- gay! or anything. I like girls! I do!”

She put her hand on his arm.

“Hey- look at me for a second. We are not in court, and I never 'accused' you of being gay. That would be a very funny reality TV show, but not what is happening right now. Listen, theoretically if you were gay that wouldn’t be bad! And I wouldn’t be… whatever you.. think that I would be? I mean- however you are afraid I would act in a negative reaction to it? I would try to be here for you, and be as supportive as possible.”

He didn’t believe her.

“Ok, sure.”

“Peter.”

“What? You’re going to tell me that you would honestly be friends with a queer person- be friends with me if I was... not... normal?”

She was taken aback by his tone, the word he had used, and the way he said it, felt like a weight dropping on her shoulders.

“Oh. would you… not?”

It was her turn to seem nervous.

“What?”

“Would you- stop being friends with someone for liking someone that they… I don’t know… shouldn’t... would be the word I guess?”

Why, in this situation, was she nervous? Oh. His fear was replaced with guilt.

“No.”

“Ok.”

“So… are you… do you… why were you scared?”

“... Why were you?”

She expected a joke from him, something along the lines of “touché".

“Are you… gay?”

“No.”

Yeah, he didn’t believe her.

“Uh-huh”

“Really, I’m not. I’ve liked boys, but also... I've had feelings for girls. I’m not… straight. So I just want to let you know that it’s okay if you aren’t too.”

“I never s-“

She smiled at him with a bit of pity, she had been there. The self-loathing, the feeling of walking on minefields with so many people in your life.

“You are…”

She paused.

“I am… what?”

“Give me a second I’m trying to find the perfect word.”

“… Okay?”

“Wonderful.”

That was not exactly the word he was expecting. Like, at all.

“Huh?”

“That’s the word. Wait- let me start over. You gotta look me in my eyes as I say it, because it’s gonna be really poetic.”

“Uh… should I be scared?”

“No. Maybe a little. No.”

“… Okay.”

He looked at her.

“You are… wonderful.”

“Oh... Thanks?“

He looked away again, to be honest, he was a bit uncomfortable. He rarely received compliments, especially ones that seem so... genuine.

“I’m not finished, look back at me, just for a second. You are so wonderful- and I will support you as whatever you are! I want you to know that I can- I can barely even think of something you could do that would make me genuinely hate you- like… maybe if you Dahmer-ed people or like chopped up a-“

He found this was amusing, yet disturbing.

“Y/N?”

“Sorry- I just- the fact that you thought, even for a second, that I could hate you… is just-“

“I’m sorry”

“No! Stop it. Don’t be sorry.”

She stared at him expectantly.

“What do you want me to-“

“Take it back! The sorry!”

“How?”

“Say you aren’t sorry”

“N/N-“

“Peter.”

“Ok. I’m, ya know, not sorry.”

“Good. You shouldn’t be”

“You’re weird.”

“Yuh-huh. Says the most likely, from the little information I've gathered, bisexual in denial who also happens to be the fastest boy on earth who had to slow down exponentially to interact with other people who also, also, happens sitting on a roof in the dead of winter with me.”

“What’s by smexual?”

Something about the way he attempted to repeat her words must have been hilarious, he thought, because here she was, sitting in front of him, in a fit of childish giggles. He would smile if he weren't so confused.

“No- that’s not- what I said- it’s… wait!”

“What?”

“You’re tryna get me off topic!”

“Am not!”

“Are too!”

“Am not!”

“Am not!”

“Are t- shit.”

“HAHA! Victory is a sweet dessert... wait is that even the saying? Still, I win you lose, nerd.”

“Ok, okay! go on.”

She was attempting to gather herself to give off a less jokey aura. It was half working, the "am not! are too!" argument a few moments ago made it hard for him to take her seriously, but he could tell it was important to her that he did, so he tried his best.

“You have to look at me again. just for a second.”

“I sw-”

“Just do it? Please?”

His attempt to put up a fight was thwarted by her small "please". He was pathetic.

“Okay.”

He looked at her.

“You…”

“Me… or- wait- I…”

“Are w-“

“Wonderful, yeah yeah. just get to the n-”

“No.”

“… No?”

“When you say it it doesn’t encapsulate it. It sounds silly.”

“Ok little miss ‘you art thou wonderful’, how would you have me say it?”

“I am you wonderful?”

“What?”

“You called me ‘little miss you are you wonderful’ what does that-“

“Ok! Would you just- shut up and call me wonderful one more time, please?”

She looked at him and blinked. That sentence surely came off as less ironic than intended.

“You are wonderful.”

She grabbed his face, in a half-joking manner. Her grab smushed his cheeks and she couldn't help but laugh a bit when she did it. Even though it was clearly a bit, he was still flustered.

“W-“

She shook him a bit.

"Shut up 'cause I'm about to say some beautiful and true shit. You are wonderful. You are wonderful. You are wonderful. You are absolutely, unchangingly, and irrevocably wonderful and there is absolutely nothing you can do about it, Maximoff.”

After saying what she would (in 40 years or so) recall as a painfully John Green-ish statement in her blunt and matter-of-fact manner, she let go of her semi-ironic hold on his pink cheeks. Were his cheeks pink because it was absolutely freezing, or because his heart was beating faster than he had ever (and would ever, mind you) run, you ask? No comment.

“Wow.”

“Wow what.”

“You do say it better than I do.”

“Did you like how I stressed different parts of the sentence each time? I thought that was a nice detail.”

“Wow.”

“So I’ve heard.”

“Wow.”

Did his voice just... break a little?

“Peter?”

“Uh- yeah?”

Was he a little... sniffle-y? She was now very concerned.

“Are you okay?!”

“Oh- um... yeah!”

No! No he was clearly not! He was sniffling!

“Really? 'Cause, you don't seem it.”

“It’s just- I just- wow.”

“Wow, what!?”

“That was just- uh-"

“Just what? It really wasn't that fancy, you seem much too impressed with me. Oh my God, was it terrible?”

“I mean it was really corny but w-“

“I swear to God if you say 'wow' one more time I may have to add ‘use of the word wow too much’ to the list of things that could make me hate you. Right next to the Dahmer stuff. That was a joke. Your use of the word wow is only mildly perturbing. Sorry."

She was panicking "just a bit".

“I’m sorry, I mean I’m not sorry. Sorry. Shit! sorry! I mean I’m not!”

And he was absolutely... full-on crying at this point.

“Peter.”

“Yeah?”

He was looking down at his mittens. Not that this is important, but they were very pretty mittens.

“Look at me, you klepto.”

He didn’t.

“You know- I’ve been hearing a lot of that 'look at me' stuff from you today. I mean- the klepto part is new-“

“Peter.”

“What?!”

He peaked up at her.

“Talk to me. Please, you're kinda scaring me, let me help.”

“I’m not sad!”

“You’re crying!”

“Yeah but not from the sads!”

“… The ‘sads’?”

“You know- when you get sad! It just means being sad! I don't- that’s what Wanda calls it, not me!"

He wiped his nose, tears still running down from his puffy eyes to his reddened cheeks.

“What are you crying from?”

“No one’s ever called me wonderful before.”

“I'm sorry! I did a few minutes ago and you didn’t cry!”

“No! You can't 'sorry' me if I can't 'sorry' you! And- yeah but that doesn’t count!”

“Why?”

“Because it only felt big when you said it the certain way!”

“What way!?”

“You look at me, you grab my cheeks-“

“I'm sorry about that by the way I was j-“

“No! It’s really ok! Do it whenever! I mean don’t do it whene- shut up!”

“I’m not even talking! You're the one talking!”

“You look at me, you grab my cheeks, and you go: you are wonderful.”

“Yeah???”

“No one ever called me that before!”

"Peter, I- well- they- they should! They should! More often! Then the amount that it happens now! I think. In my opinion."

"Or really looked at me like that!”

“Looked at you like what, Peter?”

“Like I was somethin’!”

“Well, you are… ‘somethin'! Whatever that means! And- I think you deserve to be looked at as such!”

“See?”

“What!?”

“You just-“

A strangled sob escaped from his throat. He didn't know how to explain.

“Pete.”

“Ew. I hate that nickname.”

He crossed his arms over his chest like a toddler, trying to completely ignore the fact that he was an emotional wreck.

“Peter.”

“Yeah?”

She opened her arms and gestured for him to come closer. He was hesitant at first- but gave up all the reasons he shouldn't move to be closer to her in exchange for the promise of comfort she was offering him. He crawled over to her and curled up in her arms. The way she held him made him want to cry more. Who does she think she is- holding him like he was worth holding? With her chin sitting on top of his hair? Letting him do that gross cry sob with the spit and the snot into her only winter coat? Rocking him, and shushing him, and petting his stupid, silver hair? She was warm, too! The audacity of this woman.

When Erik brought Charles into his office to grab a chess set, they saw the two in the window. For a moment Charles considered telling Peter and Y/N to get off of the high platform, seeing as the two were the reasons the "no sitting on the roof" rule was enacted in the first place (neither of them were coordinated whatsoever). Charles quickly dropped this notion when he saw the look on Erik's face, Charles could tell it made him so happy to see Peter be held like that, cared for like that. Erik's expression made Charles want to both tell Erik that he is the most precious thing in the world, and make fun of him (look at Mr. Metal, gone completely soft). Possibly he could do both at the same time. But for now, he is just going to pretend he didn't see the two outside of the window, and have Erik grab them their game, go to the living room, and pretend not to have read Erik's mind when he inevitably asks him how he always manages to pick the white chess piece at "random".

#is this even good#i wrote this instead of an essay#peter maximoff#peter maximoff fluff#peter maximoff x reader#me 🤝 commas#me 🤝 ... okay#the quality of this fic 📈📉📈📉📈

59 notes

·

View notes

Note

Maybe its not supposed to be a racism allegory. It still works for the story and worldbuilding. Just like Beastars, where attempts to compare it to real life won't work since the problems the characters face are really specific to their own society and their own nature, so the story wouldn't make sense if you replaced them with humans. But if the allegory really was the author's intent, then you're right and it was poorly done.

alright. i want to give you the benefit of the doubt, but there is a bit of ignorance to what you say. so i’ll be as thorough as possible about my thoughts.

authorial intent is really powerless when it comes to what a piece of media says or does. if a piece of media harms, but the author did not mean it to harm, does that make the harm any more less?

content creators and content consumers alike are likely familiar (and if not, should be) with the notion of ‘death of the author.’ from tvtropes’ summary of the concept:

Death of the Author is a concept from mid-20th Century literary criticism; it holds that an author's intentions and biographical facts (the author's politics, religion, etc) should hold no special weight in determining an interpretation of their writing. This is usually understood as meaning that a writer's views about their own work are no more or less valid than the interpretations of any given reader. Intentions are one thing. What was actually accomplished might be something very different. The logic behind the concept is fairly simple: Books are meant to be read, not written, so the ways readers interpret them are as important and "real" as the author's intention. [...]

Bottom line: A) when discussing a fictional work with others, don't expect "Author intended this to be X; therefore, it is X" to be the end of or your entire argument; it's universally expected that interpretations of fiction must at least be backed up with evidence from within the work itself and B) don't try to get out of analyzing a work by treating "ask the author what X means" as the only or even best way to find out what X means — you must search for an answer yourself, young seeker. Writing is the author's job; analyzing the work and drawing conclusions based on it is your job — if the author just gave away the answers every time, where would the fun be in that?

>interpretations of fiction must at least be backed up with evidence from within the work itself. okay, fine. so i argue brand new animal is a racism allegory. let’s look within the show to find evidence of this.

from episode 9: “But Nazuna wants to give a glimmer of hope and dreams to the beastmen who’ve been persecuted and suffered for so long.”

'the beastmen who have been persecuted.’ what exactly does that mean? persecution as defined in mac’s dictionary function (which cites new oxfords english dictionary): hostility and ill-treatment, especially because of race or political or religious beliefs.

the beastmen are not oppressed because of who they believe in, so not of religious beliefs or political beliefs, with the exception of believing they deserve rights, which plays into... that they are persecuted for race.

i dont really think i need to back up that statement, but for the sake of a sound argument, this is from episode 1.

it’s clear that this human dude has a distaste for michiru here because of what she is, a beastman, which is essentially what she is, her race. hence racial persecution, or, racism.

in your own words, “attempts to compare it to real life won't work since the problems the characters face are really specific to their own society and their own nature, so the story wouldn't make sense if you replaced them with humans.”

is the above exchange really so displaced from real life? this kind of thing really does happen; being targeted and even beat up simply for existing as you are is not something that is so specific to only the world of bna.

sure you may argue that replacing humans into the whole story would not make sense and well sure, yes. it is indeed a work of fiction so it won’t be a perfect replication of the human experience. but there is enough situations like the above to argue it mirrors racial prejudice in real life.

the evidence is there, so with the philosophy of “death of the author,” it is arguable this piece of media exists as a racial allegory, whether or not trigger wrote it to be that way. if they somehow did not have real race/minority relations in mind when writing this, which i would find very hard to believe, than it has still become bigger than them. because people who face racism will relate to scenarios such as beastmen being the target of hate crimes like the above, and nothing the authors meant to do really changes that feeling.

when such a scenario as above is set up in the very first episode to give you a picture of what this persecuted group experiences, while simultaneously likening itself to what minorities in real life experience, the treatment in following episodes of said group will reflect back as commentary on real life groups whether or not the authors intended that.

in bna’s case it’s rather damaging with implying this minority group is prone to rage and destruction because of their nature or dna:

episode 9: “Beastmen are easily influenced by their emotions. When their frustration builds up, the slightest thing sends them into a fury, causing confusion.”

episode 10: “The stress from multiple species invading your habitat accumulates subconsciously. In that situation if there is a powerful mental shock, the enrage switch in beast [dna] is set off, and their fight instincts take over.”

this is where you may argue in your own words “the story wouldn't make sense if you replaced them with humans.” which, yes that is true, but again this is fiction. the dynamic they establish in that first episode with beastmen being persecuted by humans is one founded in real race relations so the show at large becomes a vehicle to which it addresses race relations.

ep 10: “They’re [the drug vaccine that cures beastmen of being animals] made to subdue beastmen who have turned savage.”

goodness this almost becomes about eugenics! which is another movement founded on racism and other -isms!

the word “savage” generally refers to wild, violent unconfined animals, which, fine, i suppose, after all these ARE animal people in the show. but the show has established this animal people group as a targeted victim minority. historically in real life, the word “savage” has been a label used to describe many persecuted groups, like indigenous peoples or african americans, in a way to dehumanize them by comparing them to animals and force the idea that they are uncivilized while making the people in power feel more justified about their rough treatment of the targeted group.

i suppose arguably they are using the word “savage” to describe animals as the word originally was intended, but after establishing the framework of these animals as being persecuted peoples, do you understand the implications? are they basically saying yes, targeted minorites, are savage? admittedly i will say that that idea is a big jump, but even if you stick to the world of the show, basically this establishes that everyone is at the mercy of their genes turning them bad... not a great message.

i kind of went beyond the scope of what you addressed in your message, but wanted to show an example of how i think it is very important to consider how a piece of media can very easily become bigger than its creators, and that you cannot hide behind authorial intent saying otherwise when media expresses potentially damaging ideas.

to reiterate the line from tvtropes: Intentions are one thing. What was actually accomplished might be something very different.

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

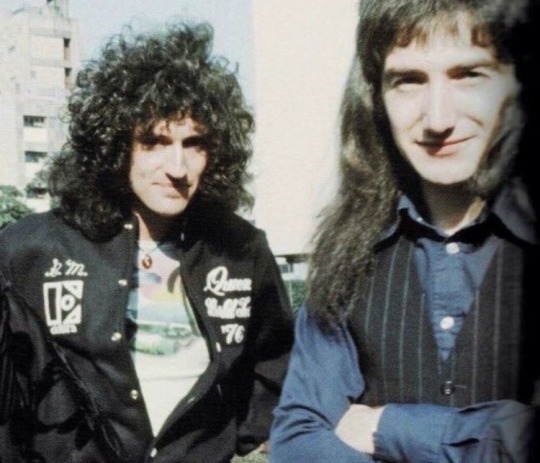

Starstruck: Part 17

Brian May x Fem!Reader

This is Part 17 of a multi-part fic. Click the links below to read the Masterpost, the previous part, or the next part of the fic :)

Masterpost / Part 16 / Part 18

Summary: When studying at Imperial College in the 1970s, your path is crossed by a beautiful boy as much in love with the stars as you.

Warnings: swearing, sentiments of sadness

Historical Inaccuracies:

SO. This is more of a disclaimer than an inaccuracy. But it’s very important...

I have written Mary’s character on basis of Lucy Boynton’s portrayal of her in Bohemian Rhapsody. I make no assumptions concerning the relationship between Freddie and Mary, and nor do I condone the things Mary has done in the wake of Freddie’s passing.

Please remember that this is but a fictionalisation. But anyway. I’m not here to talk about that; I’m here to write fanfic. Let’s go!

Word Count: 2.6k (can i get three cheers for the shortest chapter ever)

⁺˚*·༓☾ ☽༓・*˚⁺

You found her soon enough. She hadn’t even made it fully up the stairs.

A pitiful sight, she was, sitting with her knees pulled up as she wept quietly into the velvet of her trousers.

“Mary,” you began gently, and she lifted her head.

Her eyes were puffy, and tears had drawn angry red lines down her round cheeks. Her hair, which had previously been up, fell about her face in blonde wisps as her lower lip trembled and her eyes filled anew with tears.

You made your way over to the corner where she sat and she watched you raptly, like a frightened animal. You knelt beside her.

“Hey, what was that all about?”

Mary only shook her head, blinking rapidly in an attempt to stem her tears.

You offered her a hand up, and after a few moments of contemplation, she took it and stood.

She stared at you a moment before rivulets came running down her face again.

“Come on,” you said. “Let’s get some air.”

You led her up the final stairs and pulled open the door at the landing, guiding her outside onto the rooftop terrace.

The night air was cool, and from the heated rush of emotions that still seemed to cloud your mind to the giddiness that still occupied your stomach, the breeze on the roof was one you welcomed.

Mary seemed to relish the sudden cold as well, going as far as to lean out over the railing and close her eyes in the onslaught of the wind.

Thinking that you should probably not allow her to do any leaning given the mental state she was presently in, you came to stand by her side.

“Do you want to tell me about it?”

Anger flashed across her face, and she wiped her eyes with a frustrated air, only more infuriated by the fact that she was crying.

You were about to assure her that she needn’t say anything at all when she blurted,

“I found Freddie with another man.”

“Oh,” you said. You pressed your lips together, trying to gauge how it was you were to handle this.

“I just can’t believe that he’d lie to me.”

You were reminded of Deacy’s comment about Freddie being ‘nearly pathological’ with respect to lying, but that was hardly helpful right now, and you could only imagine the crushing betrayal Mary must have felt.

“I can believe that he would lie,” she elaborated, fingers curling around the railing, “but not to me. I just— oh, I suppose I thought I was different.” She gave a shudder. “I’d had the feeling that something wasn’t quite right, and I tried to talk to him, tried to tell him that he could tell me anything, and that even if I was mad about whatever it was when he told me, I wouldn’t stay that way.”

Mary turned to you, and the wind tossed her hair wildly, and with the way her eyes still ran with saltwater, she seemed a maiden from some sort of Greek tragedy.

“I love him,” she went on. “But I’ve always felt that I loved him more than he loved me. Now I understand why.”

She slumped to the ground again, her expression dark. “I’m not even angry that he didn’t come out to me. I understand that, because how the hell do you begin to tell your fiance that you want to break of the wedding because you’re gay?

“Freddie’s got this kindness, and sometimes, it’s like he’d lie to a court if it meant that he spared the feelings of those he loves. So I guess, in a way, he does love me. I only wish he’d have tried to break it off with me, instead of waiting until I walked in on him.”

She sighed, and you sat down across from her, folding your legs beneath you.

“So, what now?” you asked, because it seemed that Mary had thought a lot about this already.

But she dropped her head to her hands. “That’s the one thing I can’t work out. Where do I go from here?”

“Have you talked to Freddie, properly?”

She shook her head. “It’s going to take me a long time to forgive him. I just hope he knows why I’m angry, and that it’s not because he’s gay.”

There. That was it. That was where she had to go. “Maybe you should tell him that.”

Mary looked at you, her face wrought in scars of mascara and eyeliner. She lifted her chin and nodded. “You’re right.” She chewed her lip a moment. “But not tonight. I don’t think I can do that.”

You nodded in understanding, because with the way sobs had wracked her body, there would be no energy left for her to have a conversation with Freddie without it dissolving into a bitter argument, even with good intentions at heart.

“Y/N, would it be okay if I stayed in your room for the night?”

“So long as you promise me you’ll talk to Freddie tomorrow,” you said. “Don’t leave him wondering.”

“Yeah.”

You stood. “Let’s just go, then. It’s past midnight anyway.”

Later, when Mary was sound asleep on one of the beds, bundled in the various extra blankets you’d scavenged from cupboards, you lay with your eyes wide open. You’d been kept awake by the sounds of the dwindling party upstairs, which had carried on for long after the scene had been abandoned by its host.

You wondered where Freddie had got to.

And where Brian had.

You’d considered going to find him many times, and had even gone so far as to stick your feet out of bed and set them on the cold hardwood floor, but in the end, you’d made up your mind to do what you always did: nothing.

He’d left you standing in the dance hall, without so much as recognition in his eyes for evidence of having kissed you. And now he was going to tell you that he’d meant nothing of it, a rush of emotions in an exhilarated situation, and you couldn’t bear to hear that.

You’d rather be left wondering than have such a finality imposed upon your mind.

⁺˚*·༓☾ ☽༓・*˚⁺

It had been days, now. They’d been tiptoeing around each other for days.

It was ridiculous to the point where I began to feel the need to take matters into my own hands.

The situation was now ultimately worse than it had been before, because very obviously, something had changed. And I’d wager that something had happened on the first night of tour. They were different now, almost shyer, more fragile in their vulnerability to each other’s charms.

He had pined for her since the late sixties, she had been oblivious since day one, and I doubted that, despite their respectively vast vocabularies, either of them knew the meaning of the verb ‘to converse’. It was all longing looks and unuttered promises, a brush of a hand and staring pensively when the other was unawares.

I was almost offended that they couldn’t pull themselves together, when they were fortunate enough to have each other.

Veronica and Robert would get farther and farther from me as each day of tour escorted us more remotely from London. It hadn’t been an option to bring my wife and our tiny child with us on tour, so I could do nothing now but miss them.

But our two resident idiots, Y/N and Brian, did have each other. And they took it completely for granted.

The open road was quiet and dark, and seemed half-asleep, the trees that blurred past the window swaying to some secret song. A flock of birds streamlined the puffy clouds overhead as the moon greeted the sun in its eternal celestial shift, light yielding light to comfort the earthly beings who feared the darkness. Though I did not fear the dark as such, it was easy to imagine lurking figures between the lone houses by the roads, creeping souls amongst the woods by the road; there was something consuming about this early-morning quiet.

On a stop between Bristol and Cardiff, I left the loos to find Freddie smoking by a payphone, notably absent from the rest of our entourage.

The morning air was chilly, and I wound the scarf around my neck in its second loop, buttoning up my jacket with a shiver. No one was out here other than out of necessity, so I made my way over to Freddie and leaned against the wall beside him.

I turned to face him. “How are you?”

Freddie pursed his lips, tapping ash from his cigarette. “Not at my most fabulous, dear.”

I nodded understandingly, burying my face further into the scarf. “It’s okay, you know. You can’t always be.”

“But that’s why I became Freddie Mercury,” he said quietly, his words nearly carried away by the wind. “I became a legend so I wouldn’t feel like this.”

“Freddie,” I began, “I’m pretty sure being legendary means you have a lot more to feel than you would otherwise.”

He smiled a thin-lipped smile, tossing his spent cigarette into the ashtray mounted atop the rubbish bin. “You are of course right, darling, but right now I’d give anything to feel nothing at all.”

“You don’t mean that.”

Freddie sighed. “I don’t know what I want.”

It was despair in his voice; I recognised it. And I understood it. Because where do you start if you don’t know what you’re working toward?

I placed a hand on his shoulder and he turned his sad brown eyes on me.

“You’re a legend, Freddie,” I reminded him. “You’ve got forever to figure it out, okay?”

He nodded.

“And you can talk to me if you need to.”

“Thank you, Deacy,” he patted my hand. “I think I’ll keep a bit to myself for a while, though, at least until we reach the city.”

“Okay.”

“Now, let’s get out of this cold. I’m freezing my tits off!”

I laughed. “Okay, Freddie.”

And though the open road was quiet and dark and I missed my wife and son, I had my friends. The second half of my family.

⁺˚*·༓☾ ☽༓・*˚⁺

You ached to kiss Brian again. To wind your fingers through his hair. To hold him close, because with the worry that wove itself through his brow on behalf of Freddie, he looked so lost, so far away, as though he needed someone to bring his floating self to the ground where his thoughts could wander amongst the living, and not dwell up in the sky with that which he had lost.

Perhaps that was why he looked to the stars so often; he’d lost so much, and they were a constant.

He deserved to have something brought back to him. And if you could return to him some of the light in his eyes instead of stealing it away, then nothing in the world would make you happier.

The mornings on the bus were tense, to say the least.

Without discussion, it seemed that you and Brian had established an agreement to keep Mary and Freddie apart until they had the time and privacy in which to talk. But it was a difficult arrangement, given that the tour bus was not exactly spacious. And given that it meant you had to keep your distance from Brian.

Presently, though, you came second to the efforts of protecting Freddie and Mary from themselves, which meant that Brian did as well. So for now, all you could give to him were silent glances and small smiles.

But Brian seemed to have other ideas.

On the leg from Cardiff to Taunton, just as you were getting back on the bus, someone grabbed your hand and pulled you around the corner.

You tensed, whirling around with your other fist raised, your heart hammering.

But your defenses were instantly disarmed, because there was Brian with his mass of curls in disarray from the wind, his lips parted as though he had been about to say something.

“Are you trying to kill me?!” you cried, your heartbeat still in your throat.

“No,” Brian said, “I’m trying to kiss you.”

“You’re—”

He pulled you to him, melding himself against you, and kissed you soundly on the mouth, his arms winding around you. Your response was immediate, and you leaned so far into him that he stumbled. His laughter tickled your lips, a rush of breath over your skin as he clutched you to stop you from falling with him.

But you pushed him against the wall instead, and his hands rose to your cheeks to kiss you more deeply, devouring— senseless. Precisely as you had once wished for him to kiss you.

There were so many things you wanted to say, but it seemed the most of them were covered in how you moved with him, vulnerable and uninhibited, purely driven by the desire to hold him close, to make him understand with your proximity how much it was you cared for him. How much you would never be able to explain the gravity of your affections for him.

Brian reversed your positions and only the existence of the wall and his arms kept you on your feet; you were dizzy with the surge of excitement that withered you where he touched you.

And his touch was everywhere.

His lips moved from your mouth to your jaw, from your jaw to your cheek, to the shell of your ear, and then in a tender trail down your neck. His fingertips fluttered at your sides, warm on your skin, but you shivered, because no one had ever touched you with such a gentleness as this, such desire, such love.

Then abruptly, he pulled back, short of breath and flushed from head to toe, with swollen lips and loose curls sticking up where your fingers had interfered with their natural fall.

The world spun as his eyes flickered between yours.

“I’m sorry if I scared you,” he hummed.

“You did a bit,” you replied. “We’re on the open road. It is sort of scary out here.”

“I’m sorry,” he said again. “I just missed you. I miss you. I feel like we’re apart, you know?”

You nodded mutely.

He asked softly, “We’re not keeping this a secret, are we?”

You couldn’t believe that he was asking, after everything. But you supposed that was how he was, considerate to the point where he doubted himself if the circumstances favoured you.

“Brian,” you said, “I don’t think I could hide the way I look at you if I wanted to.”

A smile flickered across his face.

Then the rain began to pour.

“Come on, back inside,” you said, taking him by the hand.

“Hang on,” he pulled you back. He lingered a moment, gazing at you aimlessly, and he looked at you the way he looked at the stars.

“What?”

Brian cradled your face in his hands. Then he pressed a gentle kiss to your nose, brushed the pad of his thumb over your skin. “I just wanted to look at you.”

You couldn’t help but smile.

“My evening star,” he murmured.

You shook your head, finding it very hard to believe that this man, who spoke so beautifully, was yours. “You’re a poet, Brian.”

His response would have been enough to flood the coldest land with a wealth of warmth, as absolutely as that which blossomed in your chest.

“And you’re my muse.”

⁺˚*·༓☾ ☽༓・*˚⁺

A/N: two more parts and an epilogue m’dears :)

taglist: @melting-obelisks @retropetalss @hgmercury39 @topsecretdeacon @joemazzmatazz @perriwiinkle @brianmays-hair @im-an-adult-ish @ilikebigstucks @doing-albri @killer-queen-87 @n0-self-c0ntro1 @archaicmusings @cloudyyspace @annina-96 @themarchoftherainbowqueen @annajolras

Masterpost / Part 16 / Part 18

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Bargain Struck

Mesopotamia!AU. Trapped in an arranged marriage, you beseech the demon Crowley to find a way to release you from it. He offers you a simple bargain, one that is far too tempting to resist.

↝Pairing: Anthony J. Crowley (ft. luscious long curls) x f reader

↝Length: 6.6k

↝Warnings: Oral (f receiving), virgin!reader, sex, dirty talk, praise kink, sacrilege lol - this is not meant to be set in any particular historical place or peoples

Cross-posted to AO3 here

There was once a man with yellow eyes and curling red hair. He had a sharp smile, and a smooth voice. He was tall, lithe, and lean, and mostly kept to himself. He had a small home just beyond the border of the town, where it seemed only the darkest of clouds would hover above. Rumours flooded the town: sometimes people would talk to him, and then they would disappear. Others would look him in the eye, then days later fall dead quite suddenly. Otherwise devoted husbands and wives would catch a glimpse of him, fall besotted, and renounce their vows.

Livestock would die. Crops turned turned to ash. Water turned to dust. Any unlucky turn of the wind, no matter how explicable, they blamed on him. They said he was a demon, a man borne of hellfire with brimstone in his soul, and the village would see no blessing from the lord until they cast off his wicked presence. Trouble was, there was no evidence of any of it. Apart from always wearing his hood up and hardly being seen in public, thus becoming the inspiration for many a children’s tale, the man was never caught doing any sort of witchcraft. People had long been burned for less, but everybody was afraid of him.

Truth is, so were you. But God had ignored your prayers for too long now, and you had to take things into your own hands. If He could not help you, then you would seek out someone who could. Even if you ended up in a great stew for the demon to gobble up, it would be a better fate than the one awaiting you now. There was someone else you feared more than any demon, and it was for this reason that you chose to follow the stories. He was said to be called Crowley, and it was in his alleged claws you put your hopes.

So once the day darkened to dusk and the village prepared for bedtime, you slipped out, quiet as a mouse, and made the journey to his home. Having never been there yourself, your path consisted solely of the details you’d heard in stories. You travelled through the trees, thickets, and even crossed a small stream you remembered one person mentioning, once they’d stopped screaming about having seen a demon in the woods. You could only imagine it was Crowley, and though fear gripped your heart, your feet kept moving until - finally - you spotted it.

Amongst the trees, a squatting little hut built of stone and wood came into view, with sagging front steps, and windows that looked blackened as though from a fire. You didn’t know if he could already hear your racing heartbeat as you tentatively walked towards the door, or if you were going to be a surprise snack that showed up to your door, but either or... it was worth it.

You raised your hand and gingerly knocked. Is that what one does when visiting a demon’s house? Do demons have a sense of social etiquette? You took a step back and regarded the threshold, all rotten wood and gnarled vines. The cottage looked one wistful sigh away from tumbling. You waited another moment, then another. Nothing.

“Hello?” You called, tilting your head to try and see inside the windows. “D-demon?” The windows reflected nothing but your face, the blackness of the inside making the image as clear as a mirror.

You felt mad. If the man were just a regular old bloke, you’d be the one awaiting the match. Still, if you were right, it was too late to turn around now. Perhaps he was a more formal demon, you thought. You straightened your back and lifted your chin, and spoke as commandingly as you could, as though you were speaking to the house itself.

“I am here to beseech the demon Crowley.”

A pause. Then a soft creak. The door then swung open quite suddenly, revealing a hooded figure as it banged against the limits of the hinges. The person stepped forward. A few long curls of red hair betrayed the personage underneath. You stepped back with a quiet gasp.

“Go on then. Beseech me.” The tone was almost playful in nature, but there was an undercurrent of power in his words. You thought it best to not anger him.

You swiped your foot back and began to lower yourself onto your knees. Before your legs could touch the ground, his voice halted you.

“No, love. A woman as beautiful as you should never be on her knees. Not like this.”

You straightened your posture, confused and flushed from his words. His demonic charm seemed to already be taking its hold on you, despite having only shared a handful of words and no knowledge of what lay under the cloak.

“I... am here to beseech the lord Crowley to release me from the bonds of my fate.”

The hooded figure was so still, you thought he’d magicked himself into a statue. Then you heard the smile in his words.

“And what fate would that be?”

You let out a soft breath, eyes falling to his feet. “An arranged marriage.”

“Brilliant! Do come in.” The man drifted to the side to let you pass. You tried to peer inside before entering, careful not to allow your foot to cross the threshold for him to pull you in before you’d properly decided. But you could see nothing. Just darkness.

A hand appeared from underneath the cloak, skin smooth and soft, and offered itself to you. Seemingly harmless. You took it tentatively, stepped over the threshold and let the darkness consume you.

The dimness was warm, but not stifling. Then, a few feet away from you, a spark. And another. Then a flame burst to life within a stone pit, and the room was bathed in light. You twisted and turned to try and get an idea of your surroundings, but it looked nothing like what you’d supposed. It was... grand.

The home was lavish; handsomely carved furniture bedecked in thick furs, low tables covered in spreads of foods you’d never even seen before on shining plates. Books and and small statues and curious instruments dotted a few stone shelves jutting out from the walls, with plants and herbs claiming every spare surface you could spot.

You blinked and he was there, standing over the fire, heating something in a pot. The stew, you thought shrewdly, you were the last ingredient.

“Now then,” he murmured, placing the pot onto a stone ledge nearby. He tipped it slowly and allowed the hot liquid to pour into two matching goblets. The smell was warm and spicy, the smoke of the fire bathing the room in a haze. He stood, goblets in hand, at which point his hood slowly fell back.

The man in front of you was devilish and beautiful. The rest of his curls tumbled forward, a fiery red shade with undercurrents of gold. The yellowness of his eyes was even more striking in the firelight, but they didn’t frighten you like the stories said they would. He was tall and lithe; you could tell from the way the cloaked draped over him.

“Here. A wine of my own creation.” He handed you one of the goblets, warm to the touch, and you cradled it between your fingers as the heat traveled up your arms. Though you hadn’t intended on eating or drinking anything the demon gave you, the smell was so divine it was nearly impossible to resist. You tipped the cup towards your mouth slowly, the sweetness of the berries and the richness of the cloves and ginger flooding your senses instantly. You lowered the cup from your mouth, careful to not overdo it, and found him looking at you intently. Placing the cup on a table nearby, you sighed, ready to make your plea.

“Please, I need your help to release me from this betrothal.”

“You do not want this union?”

“No.”

“And why is that, love?”

You sat down on the furs with a huff. All of the arguments with your family went swirling through your head. It was hard to pick just one reason.

“I’ve been putting it off for years. Now they want me to marry a man who’s... cruel. I’ve seen it, he’s an evil man. I cannot belong to a man like that. I simply want to live freely without the bonds of marriage, to love freely... I’ve prayed to God asking why I must do this, and he has ignored me. They tell me it is his will, but what of my will?” Your eyes widened and you placed your hand against your mouth. “I- that was sacrilege.”

“And beautifully said, might I add. But what do you suppose I can do?”

“Well, you are a demon, aren’t you? Can’t you... kill him?”

He laughed then, a warm sound showing off two rows of beautiful teeth. You thought you’d seen two shaped like fangs, but when you blinked, his smile had already faded.

“I s’ppose I could, yes, but I made a promise to a... colleague of mine- er, not the point. What’s to stop them from finding another bloke if this one dies? And I certainly can’t kill off every eligible man in your village. You lot would have my head.”

“Then I’m trapped?” Despair filled your voice at the thought. The demon shook his head.

“No, love. We will simply have to think of a more eternal solution.”

You blinked. “And that would be?”

“Give yourself to me.”

You stuttered, the words dying in your throat. A red flush climbed up your throat to your cheeks like the tongue of a flame. “Wh-what?”

“Give yourself over to a higher temptation, and no man, no covenant will be able to pull you from it.” His voice adopted a low, velvety timbre, and your thoughts swam as the warmth and haziness of the room settled upon you like a thick blanket. However, you still felt clear-headed, so it hadn’t the wine affecting you so; it was the weight of his words that rushed over you like a tidal wave. “With your soul in my possession, you could not offer it to be bound in the sanctity of matrimony. Along with your mind, your body... Of course, your reputation might suffer. Not to mention your status regarding more... eternal fates.”

“My soul in the hands of a demon! I’d be ruined for eternity... but I’d be free.” You whispered, fingers aimlessly playing with the tassel of a cushion. You fixed him with a hard look, your human gaze unable to penetrate the attractive mask that his face presented. His words were tempting, his face desirable, but he was a demon after all, and you’d be an idiot to take his offer at face value.

“What’s in it for you?”

Crowley smiled then, his snakelike eyes glinting in the firelight; he looked as though he’d eat you whole right there and then. You shifted a bit on the bundle of furs, uncomfortable with so blatantly desirable a stare. You’d certainly never been on the receiving end of one before. He still did not reach out to touch you, but with one word, his wants were clear.

“You.”

“So you wish to possess me- how is that any different than a marriage?”

“Anybody ever tell you that you ask too many questions, angel? You’ll simply have to see for yourself.” He grunted quietly, raising a hand with long and delicate fingers. He touched your wrist gingerly, turned it over, and traced his fingertips along the exposed skin. You felt goosebumps pebble your skin. and you let out a shaky breath. His touch was light, delicate, but you felt his power thrumming inside of you. It almost felt as though the blood inside your veins was drawn towards him and his heat.

If you gave yourself to him, he would possess you, own you, mind, body, and soul. He’d turn out all hope for glory in the eternal kingdom, ravish your lust and tarnish your soul irreversibly. It was not that you simply assumed these things; you saw them. Images flashed in front of your eyes of heat, darkness, pleasure, depravity, want, satiation, and... protection. Freedom. A bond that would keep you and yet set you free. An unstoppable force.

The images slowly faded from your eyes, but his fingers did not release your wrist. His touch was feather-light as the firelight threw shadows over your skin. Your heart was racing, and it felt as though your skin was lit aflame from the moment he touched you. You felt the edges of your soul singe from the hellfire he imposed upon you.

“Make your choice.”

You felt like a rabbit caught in the jaws of a wolf. Heart hammering, you closed your eyes and breathed in through your nose and out of your mouth to steady yourself. Your soul was rejecting this devilish influence, but your heart, your mind, wanted nothing more than to give in. Even your body had less than pure intentions, as you felt yourself grow hot between your thighs. Nothing else could make you feel like this again. Not for all of eternity, and it wasn’t worth letting slip away.

“Yes.” You said, and the haze slowly began to clear. You found strength in that one word.

“Yes, what? I need to hear you say it, love.”

“Yes, I give myself, body, mind, and soul, to the demon Crowley. I surrender myself to you.”

The smile on his face was wicked, and his eyes fell to the smooth skin of your upturned wrist as his fingers made quick work of it. He traced a pattern along the visible veins, just for a few seconds, and you felt your blood answer the call, singing at his touch. Moments later, something began to appear. Rising from within your flesh came a mark on your skin; pink at first, then red, then you watched with bewilderment as the colour darkened to the deepest black. It was then that you recognized the shape - a coiling black snake. He released your wrist gently and you clutched it, cradling it in your other hand and staring as though it was someone else’s. You rubbed your thumb over the mark, but no ink stained it. No pain throbbed through your arm. No burning. It was just... there. As if it had always been.

You looked up at Crowley, understandably shocked, and his eyes gazed upon you, pleased. His features were so beautiful, yet chiseled with the intent to tempt unsuspecting prey. Like you. Even his hair acted as a temptation, soft curls tumbling forward from his hood. You fought the urge to reach out and touch them, run your fingers through them - maybe pull them, and instead watched as he raised a hand, finger tapping against his temple. The same black insignia marking his skin.

“It’s... beautiful.” You surprised yourself, but honestly, it was. The detailing on the snake was unlike anything you’d ever seen before, and as you rolled your wrist between your fingers, you could’ve sworn the scales gleamed like a real snake. Suddenly, the tail twitched, and a slippery tongue lashed out, and you gaped at your own hand.

“How-”

“Little bit of an illusion.”

“Will other people see this? Will they know what I have done?”

“No. The mark can disappear if you wish. But they will know, regardless if they see the mark or not.”

“What does that mean, exactly?”

“It’s a mark of protection, angel. Those who would otherwise have ill intentions will be forewarned.”

“So they can’t force me to marry?”

“Not unless they’re ready to take on hell itself.”

A feeling of relief suddenly flooded through you. You were beginning to understand what this bond meant; you’d given yourself to him, and yet you were still free to pursue your own will. If you had to be bonded with someone, you’d always choose the one where you’d given yourself willingly.

You looked down at the mark emblazoned upon your wrist, a smudge of ink staining your skin. Like he used the ashes of hell itself to imprint his mark on you. You’d never felt safer in your life. Your eyes flickered up to Crowley’s, drunk with the feeling.

“If my choices will now be wholly mine, I choose to take everything in my hands-” You straightened your back, fingers beginning to unlace the front corseted portion of your dress. It began to fall slack as you shifted your shoulders, revealing a white shift dress beneath it. “-including you.”

Crowley’s eyes flickered darkly. He had never seen a human give themselves so willingly to the hands of hell, but you were something different. You were temptation incarnate, and it was time that you tapped into those strengths. With his help, of course.

“Not wasting any time, are you?”

The outer layer of your dress was now pooled around your waist, and Crowley wanted nothing more than to rip it off to avenge your hips for being so tragically hidden from him. He watched your trembling hands reach forward for him, as each deft finger unknotted the bindings that held his cloak together. You pushed it off his shoulders slowly, revealing a lean, lithe figure clad in only a tunic.

“This will mark your downfall, angel.” He murmured, taking one of your hands by the wrist to stop your movements. The trembling stilled instantly at his touch. “There is still time to change your mind.”

“I said yes, Crowley. I want you. My choice.”

“Then let it be damnation upon you.”

His lips pressed against the mark on your wrist, then slowly moved up to your forearm, up to your shoulder. At this point, he had pulled you so close that you were nearly flush with his chest. His fingers were apt and skilled as they pulled off the wadded remnants of the dress, tossing it aside as though it offended him. You were left in a white undergarment, shivering, nipples pebbled from the cool air, though you felt like you were burning up inside.

Crowley’s large hands cupped your breasts, and you let out a soft moan at the feeling. His thumb ran over one of your nipples. “So sensitive already, angel. I’m going to take my time with you.”

You felt yourself grow wetter between your thighs, and an accompanying heat you had never felt before flared in your stomach. You felt an arm snake around your waist, and you were pulled to your feet. The outer layer of your dress fell from your hips, which pleased Crowley as he placed a searing kiss against your lips. Every touch made you feel feverish, which did not bode well for you once he’d had his way with you. The thought made you drunk with desire.

He took you into the bedroom, a handsomely carved bed standing right in the centre. A few books and candles dotted the shelves, all of which came alight with a swing of his arm. You swore you would never get used to that.

“Lie down for me.” Chills seemed to overtake your body at the sound of his low voice rattling deep inside your ribcage. Not wanting to remove yourself from the heat of his body, and yet wishing to comply, you stepped away from him and sat up onto the edge of the bed. You sank in the softness of the sheets, falling back with a soft sigh.

“Enjoying yourself?” He asked with that same tone of playfulness. You smirked to yourself, allowing your eyes to close for a moment.

“Isn’t that the point?”

The sudden feeling of his mouth on your inner thigh made you gasp. You moved to buck your hips at the sudden sensation, at which point he pressed his hand down against your lower stomach, holding you down. He kissed either thigh softly. “I realize this can be overwhelming for you humans, so if you tell me to stop, we stop. Yes?” You felt his teeth scrape against your sensitive skin, and your hips fought against his hand, seeking the heat of his mouth once more.

“Yes, Crowley.” You swore, eyes closing again.

“There’s a love.”

You didn’t know when he had bunched your underdress around your hips, but you had been far too distracted to even realize it was still adorning your body. Your thoughts were cloudy beyond the most instinctual drives: Crowley, touch, heat, pleasure. Luckily, he was eager to oblige.

“Please, please, Crowley..” You whimpered, feeling his hot mouth draw closer and closer to your centre. You had no previous knowledge of carnal relations, but you’d heard so many stories of how stiff, pleasureless and lifeless it could be. So far, this was by far exceeding your expectations.

His large hands gripped your thighs and spread them further apart. You flushed, the heat from your traveling all the way up to your cheeks to colour them pink. He held them firmly, leaving all hope of preserving your dignity in the dust.